We Paid $150k/Year for an Agile Coach Who Had Never Written a Line of Production Code

We Paid $150k/Year for an Agile Coach Who Had Never Written a Line of Production Code

His first week on the job he sat in on a technical discussion about Kafka consumer group rebalancing that was causing production issues. Our team had been debugging this for two days. Engineers were deep in it, debating partition assignment strategies, consumer lag metrics, offset management. Real stuff. The kind of conversation that separates people who build systems from people who talk about building systems.

Forty five minutes in, he raised his hand and asked: "But have we tried breaking this into smaller stories?"

The room went silent. Not the productive kind of silence where someone says something brilliant and everyone needs a moment. The awkward kind. The kind where twelve engineers are trying to figure out how to respond to a question so disconnected from the actual problem that acknowledging it feels like rewarding it.

One of the senior devs eventually said "this isn't a story problem, it's a partition rebalancing problem" and the conversation moved on. The coach nodded and wrote something in his notebook.

That was November 2018. He stayed for two years.

I'm going to tell you exactly what happened during those two years because I think it captures something broken about how organizations approach engineering effectiveness. And if you're living through something similar right now, I want you to know you're not crazy for feeling like the emperor has no clothes.

The Pattern

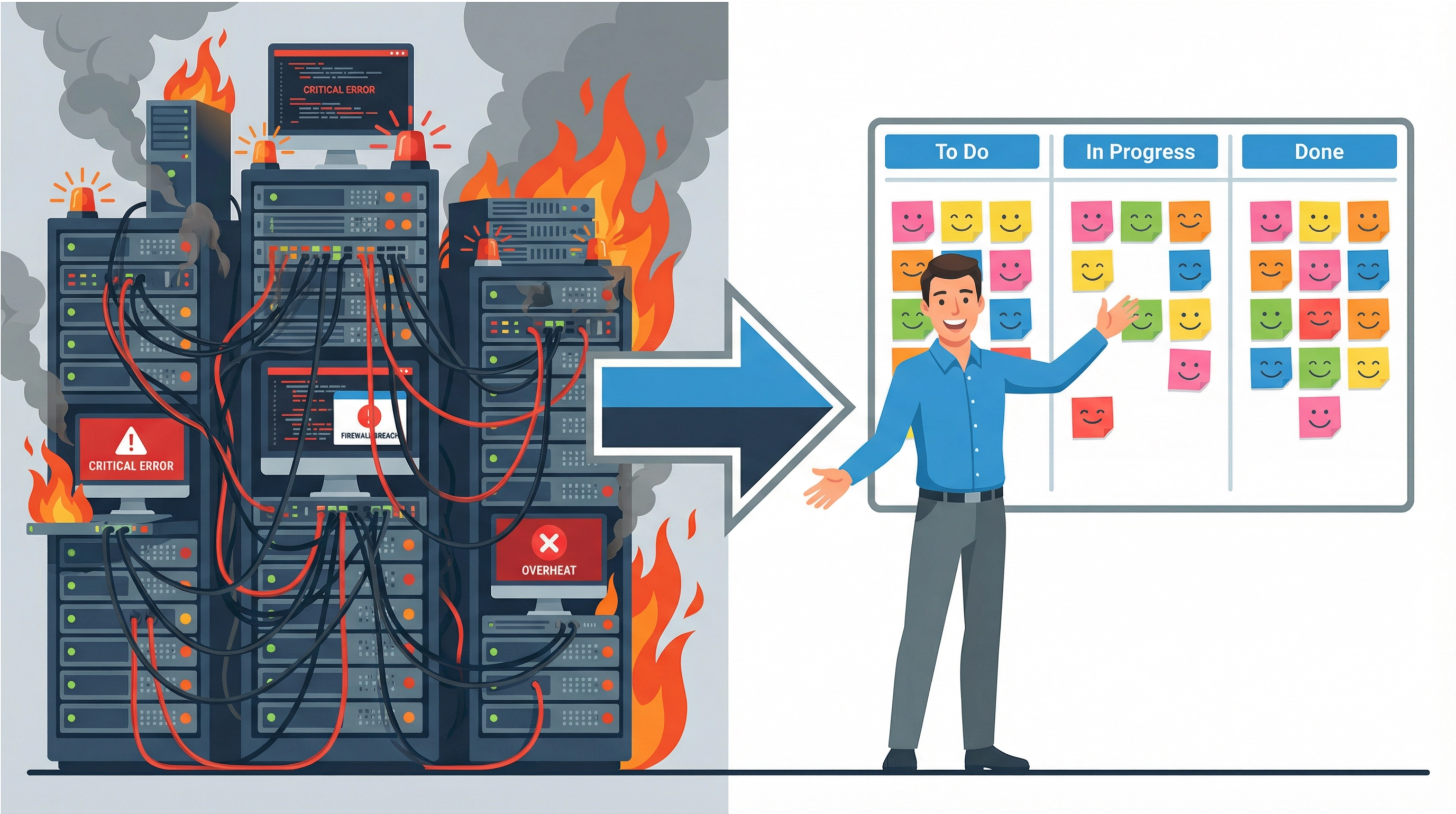

Within a month, a pattern emerged. Every technical problem the team raised got redirected to a process conversation. Not because process was the root cause. Because process was the only domain the coach understood.

Team struggling with a complex database migration from Oracle to PostgreSQL? "Let's timebox this discussion and take it offline." Take it offline to where? To a meeting he'd facilitate where he'd ask us to put our concerns on sticky notes and dot vote on them. The database migration didn't care about our dot votes.

Team debating microservice boundaries for a payment processing system? "I'm hearing a lot of technical details, but what's the user story here?" The user story was that our monolith was collapsing under its own weight and we needed to extract services before it took the platform down. That doesn't fit neatly into "As a user, I want to..."

Team blocked on a deployment pipeline issue where builds were failing intermittently? "Sounds like we need a retrospective to discuss our process around deployments." We didn't need a retrospective. We needed someone to look at the Jenkins configuration and figure out why the Docker layer cache was invalidating on every build.

Every time. Without exception. Technical problem goes in, process recommendation comes out. Like a machine that can only produce one output regardless of input.

The Coaching Sessions

The worst part wasn't the meetings. It was the one-on-ones.

He'd pull engineers aside, usually the more junior ones, for what he called coaching sessions. Thirty minutes, every two weeks. He'd ask questions like "what impediments are blocking your growth?" and "how do you feel about the team's collaboration?"

I sat in on one because a junior developer asked me to. She was confused about what these sessions were supposed to accomplish. He spent twenty minutes asking her about her career goals and what kind of work energized her. Then he suggested she might benefit from "being more vocal in sprint planning."

She was quiet in sprint planning because she was six months out of a bootcamp and didn't feel confident estimating work she barely understood yet. What she actually needed was someone senior to pair with her on hard problems and help her build technical confidence. What she got was advice to talk more in meetings.

The senior engineers had it worse in some ways. Imagine having fifteen years of experience building distributed systems at scale and being asked by someone who doesn't know what a load balancer does to reflect on your impediments. Most of them just went through the motions. Smiled, said something vague, waited for it to be over.

One of them told me privately: "I have more to learn from a five minute code review than from a year of those conversations."

The Certifications

He had all of them. CSM. SAFe SPC. ICF-ACC. ICP-ATF. ICP-ACC. A few more I can't remember. His LinkedIn looked like an alphabet soup explosion. Every few months he'd disappear for a week to get another one and come back with a new framework to introduce.

I looked into what some of these certifications require. Two day courses. Multiple choice exams. No technical prerequisite whatsoever. No requirement to have ever built software, managed a codebase, deployed to production, debugged a system at 3 AM, or experienced any of the actual challenges that engineering teams face.

You can become a Certified Scrum Master in sixteen hours. You can become a SAFe Program Consultant in four days. And then you're considered qualified to coach teams of senior engineers on how to be more effective at building software.

Think about that for a second. In what other profession do we accept that someone with zero domain experience can coach domain experts? Would you hire a swimming coach who had never been in a pool? A flight instructor who had never flown? But somehow in software engineering we decided that someone who has never shipped production code is qualified to tell engineers how to organize their work.

The certification industrial complex created an entire profession of people whose authority comes from credentials rather than experience. And organizations buy it because the credentials feel safe. You can put "SAFe SPC certified coach" in a report to leadership and it looks like due diligence.

The Retrospectives

I'll give him this: his retrospectives were textbook perfect. Clean facilitation. Everyone spoke. Sticky notes were color coded. Dot voting was orderly. Action items were documented in Confluence within the hour. He was genuinely good at running a structured meeting.

But look at the action items over six months and a pattern jumps out. Every single one was a process change. "Refine our definition of ready." "Add a pre-grooming session before grooming." "Create a new Slack channel for cross-team dependencies." "Update the sprint review format to include a demo."

Not once did an action item address a technical root cause. Not once did someone walk out of a retro with a plan to refactor the module that was causing 60% of our production incidents. Not once did we commit to paying down the technical debt that was making every sprint slower than the last.

Why? Because he couldn't evaluate technical suggestions. When an engineer said "we need to refactor the payment service because the coupling between the transaction processor and the notification system means every change to one breaks the other," he didn't have the context to understand whether that was a real priority or an engineer gold-plating. So he defaulted to what he could evaluate. Process.

The retros became a ritual where engineers surfaced real problems, the coach translated them into process changes, and the real problems persisted. Sprint after sprint. Month after month.

The Production Incident

The moment that crystallized everything happened on a Thursday night. A payment processing service started throwing intermittent 500 errors. Not enough to trigger the main alerting threshold but enough that roughly 3% of transactions were failing silently.

The on-call engineer caught it around 9 PM. By midnight we had four people on a call trying to trace the issue. It turned out to be a connection pool exhaustion problem caused by a retry mechanism that wasn't releasing connections on timeout. The fix was straightforward once we found it but finding it took fourteen hours because the service had been patched so many times without proper refactoring that the connection lifecycle was spread across six different classes with no clear ownership.

Everyone on the team knew this service was a disaster. We'd been flagging it in retros for months. The tech debt was documented. The risk was known.

The coach facilitated a blameless postmortem the next day. Good practice, absolutely. But watch what happened.

Engineers started explaining the technical root cause. Connection pool management, retry logic, timeout configurations, the accumulated tech debt that made the service fragile. Real, specific, actionable information about why this happened and what would prevent it from happening again.

The coach listened, nodded, and then started steering the conversation. "How can we improve our incident response process?" "Should we revisit our on-call rotation?" "What about our monitoring and alerting thresholds?"

Valid questions, sure. But he was driving the conversation away from the root cause and toward the process around the root cause. Because that's where he was comfortable. That's where he had authority.

The tech debt in that service? He summarized it in the postmortem document as "legacy system challenges" and moved on. A fourteen hour outage caused by a specific, known, fixable technical problem got reduced to two words that communicated nothing and committed to nothing.

Six weeks later the same service caused another incident. Different symptom, same root cause. The retro produced more process changes.

What $150k Could Have Bought Instead

For $150k a year we could have hired a senior engineer. Not a staff level architect. Not a principal. Just a solid senior engineer who understood distributed systems and could actually help the team.

Someone who could look at that Kafka configuration and say "your consumer group is rebalancing because you have more partitions than consumers in one instance and fewer in another, here's the fix."

Someone who could pair with the junior developer on her first production service and show her how to handle connection pooling properly instead of asking her about her impediments.

Someone who could sit in that postmortem and say "the connection pool is leaking because the retry handler doesn't implement the circuit breaker pattern correctly, we need to fix this specific thing in this specific class."

Someone who could review pull requests and catch architectural mistakes before they shipped instead of reviewing sprint boards and catching process deviations.

Someone who earned the team's respect by demonstrating competence in the domain the team operates in rather than in a parallel domain the team didn't ask for help with.

I've worked with coaches like this. Technical people who moved into coaching roles after years of hands-on engineering. They exist. They're rare because the certification path doesn't select for them, but they exist. And the difference is night and day.

A technical coach looks at your retro board and says "three of your top five issues trace back to that payment service, let's talk about a refactoring plan." A non-technical coach looks at the same board and says "let's try a different retro format to get more engagement."

Same data. Completely different interpretations. Completely different outcomes.

Why This Keeps Happening

I've thought about this a lot and I think there are three reasons organizations keep hiring non-technical coaches for technical teams.

First, the certification system makes it easy. There's a clear pipeline. Take the course, pass the exam, get the credential, apply for jobs. The pipeline produces far more non-technical coaches than technical ones because there's no technical barrier to entry. Supply and demand does the rest.

Second, leadership doesn't know the difference. When a VP of Engineering sees "Certified Agile Coach" on a resume, they don't think about whether that person can debug a distributed system. They think about transformation metrics, team velocity, delivery predictability. The coach gets evaluated on process outcomes that are easy to measure rather than technical outcomes that require domain expertise to assess.

Third, and this is the uncomfortable one: some organizations want a coach who won't challenge technical decisions because challenging technical decisions requires understanding them. A non-technical coach keeps the peace. They facilitate, they don't disrupt. They make the process smoother without questioning whether the right things are being built in the right way. It's comfortable. It feels like progress.

What Actually Works

After twenty five years in banking tech I've seen what actually makes engineering teams more effective. It's not complicated. It's just not what the certification industry sells.

Technical mentorship. Senior engineers helping junior engineers through real problems. Not career coaching. Not impediment discussions. Sitting together, looking at code, building things. The most effective "coaching" I ever saw was a staff engineer who spent two hours a week reviewing architecture decisions with the team. No framework. No certification. Just domain expertise applied to actual problems.

Autonomy with accountability. Teams that got to decide how they worked, what process they followed, what meetings they needed, consistently outperformed teams that had process imposed on them. The catch is they also had clear ownership of outcomes. Freedom without accountability doesn't work. But neither does process without freedom.

Leadership that removes real obstacles. Not a coach who "removes impediments" by scheduling a meeting with another team. Leadership that actually has the authority and technical understanding to say "this system needs to be rebuilt and I'm going to make the case to fund it." The kind of impediment removal that requires organizational power, not facilitation skills.

Reducing unnecessary overhead. The best performing teams I worked with had fewer meetings, fewer ceremonies, and fewer process artifacts than the worst performing teams. They weren't chaotic. They were focused. They communicated more through code and documentation and less through rituals.

The Real Question

The coach I worked with was a good person. He was genuinely trying to help. He cared about the team and spent his weekends reading about coaching techniques and facilitation methods. This isn't about him as an individual.

It's about a system that puts well-meaning people in roles they're not equipped for and then blames the team when it doesn't work. It's about an industry that sells certifications as expertise and organizations that buy them because they look good in a transformation report.

If you're an engineering leader hiring an Agile coach, ask yourself one question: can this person help my team solve the actual problems they face? Not facilitate a conversation about the problems. Not reframe the problems as process issues. Actually help solve them.

If the answer requires technical understanding and the candidate doesn't have it, you're not hiring a coach. You're hiring a meeting facilitator with an expensive title.

And if you're an engineer sitting in your third coaching session this month wondering why someone who doesn't understand your work is telling you how to do it better, you're not crazy. The system is broken. Your frustration is valid.

The best engineering teams I've seen in twenty five years didn't have Agile coaches. They had technical leaders who earned the team's trust by being competent in the team's domain. They had processes that emerged from the team's actual needs rather than being imported from a certification syllabus. They had leadership that understood the difference between process improvement and engineering improvement.

That's it. No framework required.

If this argument resonates, the full case against Agile's pathologies—from estimation theater to cargo cult ceremonies—is laid out in AGILE: The Cancer of the Software Industry→. It's the manifesto the Agile industrial complex doesn't want you to read.