The Psychology of the 9:00 AM Standup: Performance Theater Over Progress

It's 8:57 AM. You've been deep in a debugging session since 7:30, tracking down a race condition that's haunted the team for three days. The solution crystallizes in your mind like a perfect snowflake. You're this close.

Then Slack pings: "Standup in 3."

Your mental model shatters. You close your IDE, bookmark your stack trace, and shuffle to the conference room. For the next fifteen minutes, you'll endure eight people reciting what they did yesterday, what they'll do today, and whether they're blocked—information already documented in Jira, already shared in Slack, already visible to anyone who bothers to look.

When your turn comes, you perform the script. "Yesterday I worked on the payment service refactor. Today I'm continuing that. No blockers."

Nobody asks what "continuing that" means. Nobody offers help. The race condition you nearly solved? Not mentioned. It wasn't in the sprint.

This isn't coordination. This is psychological theater.

What Standups Claim to Be

The Agile textbook tells us daily standups exist to:

- Synchronize the team on current work

- Identify blockers quickly

- Promote transparency and collaboration

- Keep everyone aligned toward sprint goals

Fifteen minutes. Three questions. Maximum efficiency. The ultimate lightweight ceremony.

Except that's not what actually happens.

What Standups Actually Are

Strip away the Agile liturgy and you'll find something more primal: a daily ritual of social accountability designed to make work visible rather than effective.

Standups don't optimize for progress. They optimize for the appearance of progress.

They're not about solving problems. They're about proving you were working on problems.

They're not about removing blockers. They're about not appearing blocked.

The 9:00 AM standup is a daily performance review disguised as a collaboration tool. And everyone on the team knows it, even if nobody says it.

The Three Psychological Forces at Play

1. Social Pressure: The Compulsion to Report

Humans are wired to conform. When everyone reports what they did yesterday, you report too. When everyone lists tasks, you list tasks. When everyone says "no blockers," you say "no blockers."

This isn't collaboration. It's compliance.

The standup creates a daily checkpoint where your value is reduced to a 60-second summary. Miss standup twice and suddenly you're the person who "isn't engaged." Give vague updates and you're "not being transparent."

The pressure isn't to do good work. The pressure is to have something reportable.

So engineers optimize for reportable work. They break tasks down not by technical sense, but by what generates visible increments. They avoid deep work that spans days. They pick up safe, small tickets that guarantee tomorrow's standup soundbite.

This is how you get a team that closes 40 tickets a sprint but ships nothing that matters.

2. Performance Anxiety: The Fear of Looking Stuck

Picture this scenario:

You're working on a gnarly database migration. The technical design took three days. The implementation is careful, methodical work—one wrong move corrupts production data. You're going slowly by design.

But at standup, day after day, you're saying: "Still working on the database migration."

By day four, you feel it. The subtle shift in the room. The questioning looks. The unspoken: What's taking so long?

Your scrum master asks, "Do you need help? Is something blocking you?"

You're not blocked. You're doing exactly what you should be doing. But now you're defending your pace. You're explaining why you don't have visible progress. You're performing justification instead of focusing on the actual work.

This is performance anxiety. The fear that slow, careful, important work will be mistaken for being stuck or incompetent.

So engineers react. They ship the migration faster than they should. They take shortcuts. They introduce risk.

Or they invent fake micro-milestones: "Yesterday I finished schema dependencies. Today I'm implementing the first three tables. Tomorrow I'll do the remaining five."

Now the work is "visible." Now you're performing progress. Never mind that you just turned a holistic technical problem into an arbitrary checklist optimized for standup optics.

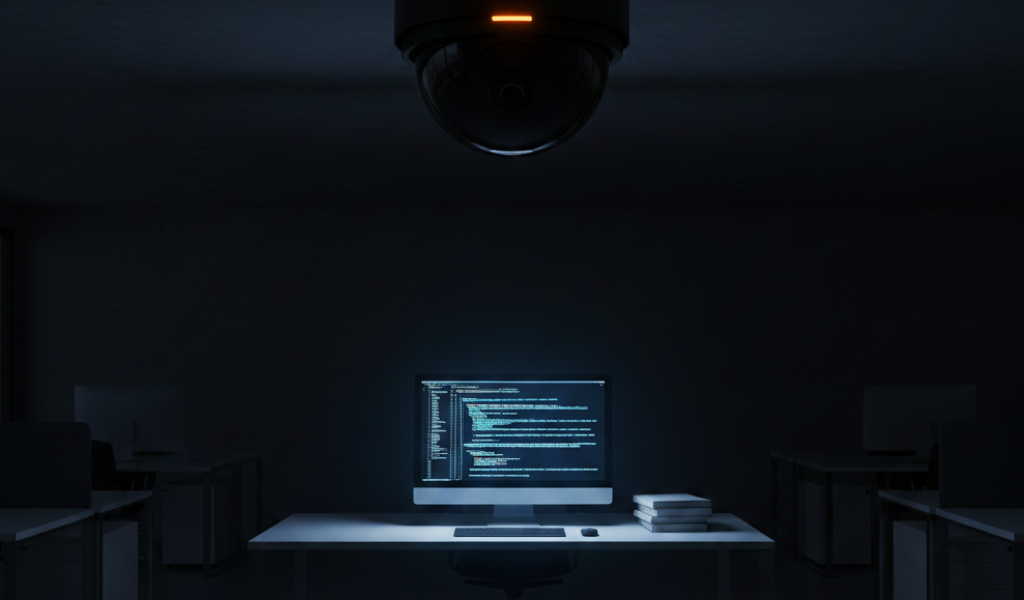

3. Subtle Surveillance: Management by Daily Interrogation

Let's be honest about what standup is for managers and scrum masters: it's a daily status check.

They're not there to "support" the team. They're there to verify the team is working. To spot who's moving, who's blocked, who's going off-script.

This is surveillance with a smile.

Consider this: Your team has standup at 9:00 AM sharp. One engineer works 11 AM to 7 PM because that's when they're most productive. They write clear async updates in Slack every day. Everyone knows what they're working on.

But they miss standup. And suddenly that's a "problem."

Not because information is missing. Not because work isn't getting done. But because they're not present for the daily check-in.

The message is clear: we trust you, but only if you show up to be counted every 24 hours.

This is why standups feel like an obligation rather than a tool. Because they are. They're a compliance ritual that signals you're a team player, you're accountable, you're here.

And if you're remote? The surveillance intensifies. Camera on. Speak when called. Prove you're not in your pajamas browsing Twitter.

The Standup Performance: A Breakdown

Let's decode what's really happening during a typical standup:

9:00 AM. The calendar invite fires. Eight engineers drop what they're doing. Context switches cost 23 minutes on average to recover from, but who's counting?

9:02 AM. The scrum master starts: "Let's go around. Sarah, you're up."

Sarah: "Yesterday I finished the user authentication stories. Today I'm starting on password reset. No blockers."

Translation: I closed tickets. I'm still closing tickets. Please don't ask me anything complicated.

Dev #2: "I worked on the API rate limiting feature. Still working on it today. No blockers."

Translation: I made progress but nothing shippable. Please move on.

Dev #3: "I fixed a couple bugs in the checkout flow and started investigating the performance issue in production. I might need help from DevOps later."

Translation: I'm doing two things because one is going slowly and I needed something to show for yesterday. The "might need help" is a pre-emptive defense in case I'm still stuck tomorrow.

9:09 AM. The pattern continues. No clarifying questions. No offers of help. No connections between related work.

9:13 AM. Your turn. You're working on a complex caching refactor. It's technically interesting, architecturally important, and invisible in the sprint board because it spans five tickets.

You say: "Working on the caching refactor. Made good progress. Should wrap up today or tomorrow."

The scrum master nods. Nobody asks what "good progress" means. Nobody asks if "should wrap up" is based on reality or optimism.

You said the magic words. You're working. You're progressing. You're unblocked.

You're performing.

9:15 AM. Standup ends. Everyone scatters. You return to your desk and spend ten minutes reconstructing your mental model.

Nothing was decided. Nothing was coordinated. No collaboration happened.

But the ritual was completed. The box was checked. Management has evidence that the team is "syncing daily."

The Visible Activity Trap

Here's the core dysfunction: standups train teams to optimize for visible activity instead of meaningful progress.

Visible activity is easy to report:

- "Closed three tickets"

- "Wrote 200 lines of code"

- "Attended two meetings"

- "Reviewed four pull requests"

Meaningful progress is harder to articulate:

- "Refactored the authentication layer to eliminate a whole class of security bugs"

- "Deleted 500 lines of code and simplified the deployment process"

- "Spent two days reading the codebase to understand why the search is slow"

- "Convinced the product team to cut a feature that would have created six months of technical debt"

The first list sounds productive in a standup. The second sounds vague, defensive, or like you didn't do much.

Teams drift toward the first list. They pick up small tasks that generate visible increments. They avoid deep work, architectural improvements, and the messy, important work that actually moves the needle.

The result? A team that's "always busy" but never makes meaningful progress. Velocity is high. Impact is low. Everyone's exhausted from performing productivity.

When Standups Become Toxic

Not all standups are dysfunctional. Small teams with genuine collaboration needs can make them work.

But here are signs your standup has crossed into toxic territory:

1. Attendance is mandatory, async updates are rejected.

If someone writes a detailed Slack update but still has to repeat it verbally, you're doing surveillance, not coordination.

2. The standup runs long because it's the only time the team talks.

If standup is where you discover blockers and make decisions, your team has a communication problem. Standup is masking it, not solving it.

3. Engineers prepare for standup.

If people are scripting their updates, rehearsing what they'll say, or checking Jira before standup to remember what they did, the standup is theater.

4. The same people dominate, the same people are silent.

If extroverts talk for three minutes and introverts mumble one sentence, you're optimizing for personality type, not information flow.

5. "No blockers" is the default answer even when people are stuck.

If engineers fear admitting they're blocked because it signals incompetence or invites unwanted "help," your standup has a trust problem.

6. Missing standup is treated as a performance issue.

If skipping standup is worse than missing a deadline, you've made the ritual more important than the work.

A Practical Alternative: Async-First Status Updates

If your team is suffering from standup dysfunction, here's a concrete alternative:

Replace Synchronous Standup With Async Updates

Daily written update in Slack or a dedicated tool:

- What I shipped or learned yesterday

- What I'm focusing on today

- What I'm stuck on or need input on

Post by end of day, read in the morning.

This eliminates context switching, removes performance pressure, and creates a written record. Engineers can update when it fits their flow. Managers get visibility. No meeting required.

For blockers and coordination, use threads and ad-hoc sync.

If someone posts "I'm stuck on X," anyone who can help jumps into a thread or schedules a quick call. You get real-time help without a daily ceremony.

If You Must Keep Standup, Make It Optional

Try this test: make standup optional for one sprint.

Tell the team: "Write your daily update async. Come to standup only if you need real-time coordination or want to discuss something."

Watch what happens.

If three people show up and the team still functions, you've proven that standup was ritual, not requirement.

If everyone still attends, maybe your team actually values the sync. But at least now it's a choice, not an obligation.

Checklist: Is Your Standup Worth the Cost?

Run through this honestly:

- Does standup regularly lead to real-time problem-solving?

- Would the team lose critical information if you skipped standup for a week?

- Do people ask clarifying questions and offer help during standup?

- Is the timing convenient for everyone's peak productivity hours?

- Can people join async without penalty?

- Is standup under 10 minutes with zero filler?

- Do engineers leave standup more aligned than when they entered?

If you checked fewer than five, your standup is a tax on productivity, not a tool for coordination.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Daily standups persist not because they're effective, but because they're visible.

Managers like them because they create the illusion of control. Scrum masters like them because they justify their role. Engineers tolerate them because objecting makes you look like a "bad team player."

But here's what nobody wants to admit: if your team needs a daily meeting to know what everyone is working on, the problem isn't standup cadence. The problem is trust, communication, and clarity of goals.

Standup is a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound.

A high-functioning team doesn't need daily status reports. They're already collaborating on hard problems. They're reviewing each other's code. They're asking for help in Slack when stuck. They know what matters because priorities are clear, not because someone recites them every morning.

Standup, in that world, is redundant.

But in a low-trust environment, standup becomes essential—not because it fixes problems, but because it creates the illusion that problems are being managed.

You're not coordinating. You're performing coordination.

And that performance comes at a cost: context switches, anxiety about reportable progress, and a slow drift toward shallow, visible work over meaningful contribution.

In addition to the psychological toll, this performance has a tangible price. You must discovery the financial impact of this daily disruption on your team here.

The 9:00 AM Reckoning

Ask yourself: what is your standup actually accomplishing?

Is it helping your team ship better software faster? Or is it a ritual that makes managers feel like they're managing and engineers feel like they're being watched?

If you can't answer honestly, you're stuck in performance theater.

The Agile Industrial Complex wants you to believe standups are non-negotiable, that skipping them is heresy, that teams who don't sync daily are doomed. But the teams shipping the best software—those with deep focus, low meeting overhead, and actual trust—often don't do daily standups at all.

They communicate asynchronously. They write clearly. They meet when needed, not when the calendar says it's 9:00 AM.

They understand that coordination is a problem to solve, not a ritual to perform.

Maybe it's time your team did too.

The dysfunction runs deeper than standup. If you're tired of Agile ceremonies that optimize for performance over progress, you're not alone. We've written extensively about how Agile became the very bureaucracy it promised to eliminate — read AGILE: The Cancer of the Software Industry→ for the full breakdown.

Or start with the basics: our manifesto lays out why the software industry needs to stop confusing process with progress.