Why Agile Estimation Is Theater: The Case Against Story Points

Your team moved forty-three cards to "Done" this sprint. Velocity up. Cycle time down 18%. Management's pleased.

Meanwhile, customers still can't export their data. That feature you shipped three weeks ago? 12% adoption rate. Support tickets climbing.

But hey—those cards moved.

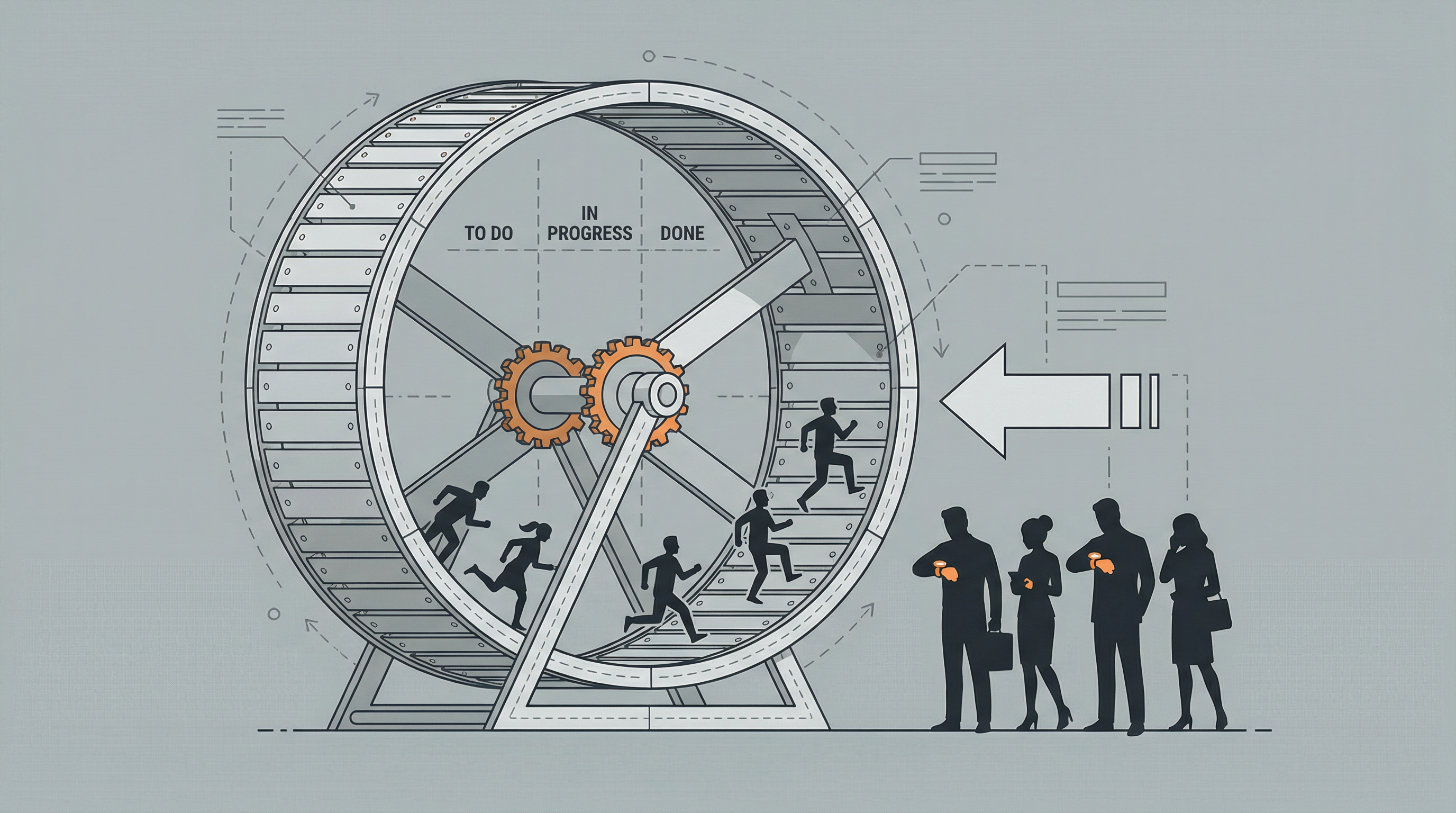

This is the core delusion: confusing visible motion with actual progress. We've built an entire apparatus—standups, boards, burn-down charts, flow metrics—that measures how busy we look. Not whether we've delivered anything worth using.

Task boards were supposed to make work visible. Instead, they made theater visible.

The Scoreboard That Measures the Wrong Game

Every team has some variation of the same board. "To Do," "In Progress," "In Review," "Done." Maybe you've gotten fancy: "Ready for Dev," "QA," "Staging."

The board becomes the source of truth. The daily standup orbits around it.

"I moved ticket 2847 to In Progress. I'm blocked on ticket 2851. I'll move ticket 2849 to Done today."

Notice what's missing? Any mention of what these tickets actually do for a human being.

The board creates a local optimization loop. Developers are incentivized to move cards because that's what gets measured, discussed, celebrated. Product managers brag about throughput. Scrum Masters obsess over flow efficiency.

Nobody's measuring whether ticket 2847 solved the problem it was supposed to solve.

Task boards make work feel tractable by breaking it into discrete units. Customer value doesn't arrive in discrete units. It arrives in messy, integrated experiences that span multiple tickets, multiple sprints, multiple teams.

You can't put "customer can now trust our data export" on a Kanban board. Too fuzzy. No clear acceptance criteria. Might take three sprints. Might take three months.

So we don't measure it. We measure the cards instead.

When Flow Metrics Become Performance Art

The flow metrics movement promised to save us. Instead of just counting velocity, we'd measure cycle time, work-in-progress limits, throughput, flow efficiency. We'd optimize the system, not just the output.

In practice, flow metrics gave us new ways to perform productivity without delivering outcomes.

I watched this at a B2B SaaS company. The engineering director got obsessed with cycle time after a Kanban conference. Mandated that average cycle time had to drop below five days.

The team responded rationally. They started breaking tickets into smaller pieces. One feature became five tickets. A bug fix requiring root cause investigation became two: "Investigate bug" and "Fix bug."

Cycle time dropped. The director was thrilled. Charts at the all-hands.

Customer-facing improvements slowed to a crawl. Nobody wanted the complex, uncertain work that might balloon cycle time. That ambitious refactoring that would've unblocked three roadmap features? Couldn't commit—might take weeks.

The metrics said the team was more efficient than ever. The product stagnated.

Optimized card movement. Sophisticated-looking dashboards. Teams that have learned exactly how to game the metrics. Not software that matters.

Scenario 1: The Sprint Where Everything Got Done (And Nothing Changed)

Sprint review I attended last year. The team was proud. Committed to eight story points, delivered ten. Every ticket moved to Done.

The product manager walked through each one:

- "We added pagination to the admin panel."

- "We upgraded the authentication library."

- "We refactored the user service."

- "We fixed the bug where the tooltip sometimes doesn't appear."

- "We added logging to the payment flow."

Each ticket had acceptance criteria. Tested. Truly done.

Then someone from customer success: "Did we ship the thing where sales reps can see which customers are at risk of churning? They've been asking for three months."

Silence.

That feature was on the backlog. Broken into five tickets. Two were in this sprint but didn't finish. One got finished but couldn't merge because it depended on the other. The other one uncovered a data model issue that spawned two new tickets.

Ten story points delivered. Zero customer value.

But the cards moved. The sprint was successful by every internal metric. Nobody got asked hard questions because the board looked great.

You deliver against internal process measures while the actual mission—helping customers do something they couldn't do before—becomes second-order.

Scenario 2: The WIP Limit That Optimized for Appearance

Different team, different company. They'd embraced work-in-progress limits with religious fervor. No more than three cards in "In Development." Forced focus. Prevented context-switching. The Kanban books said this was the path.

Then a gnarly production incident. Payments failing intermittently. Not always—just enough to be terrifying. The kind of bug requiring deep investigation, log analysis, reproducing race conditions.

One engineer started on it. Two days in, narrowed it down but hadn't fixed it. Card still "In Progress."

Three other cards also in progress. WIP limit hit. Nobody else could start new work.

The engineer felt pressure. Standup conversations got awkward. "Still working on the payment issue" day after day while the board stayed blocked.

So they paused it. Created a new ticket: "Investigate payment failure—research spike." Moved that to Done. Created another: "Fix payment race condition." Put it in the backlog.

Original ticket moved out of In Progress. WIP limit freed up. Other people started new cards. Metrics looked healthy again.

The payment bug took three more weeks to fix because the investigation kept getting interrupted.

Flow metric optimized. Customer outcome sacrificed.

What Value Delivery Actually Looks Like

Real value delivery is annoyingly hard to measure. Even harder to gamify.

It looks like:

- A customer manually reconciling spreadsheets for four hours a week now spends fifteen minutes because your export format finally matches their accounting software.

- A sales team losing deals because prospects can't try the product without a call can now self-serve trials. Trial-to-paid conversion goes up.

- A support team spending 30% of their time explaining a confusing workflow now spends 5% because you redesigned it.

These outcomes are messy. Span multiple tickets. Require talking to customers. Take time to validate. Not visible on a task board.

But they're the actual job.

Most of what ends up on a task board is proxy work. We're betting that if we complete these specific technical tasks, customer value will emerge. Sometimes we're right. Often we're not.

The ticket is not the value. The ticket is a hypothesis about how to create value.

Get the weekly breakdown

What the Agile industry sells vs what actually works. Data, war stories, no certification required. Free, unsubscribe anytime.

When we treat card movement as the victory condition, we stop checking whether our hypotheses were correct. Stop instrumenting whether the thing we shipped actually changed user behavior. Stop talking to customers after launch.

We just move to the next card.

The Institutional Blindness Problem

Task boards create institutional blindness at scale.

When everyone—developers, product managers, engineering leaders—stares at the same board, has the same standup conversations, tracks the same metrics, a shared reality emerges.

The board is the work. The sprint is progress.

Anyone who questions this gets a confused look. "But we delivered everything we committed to. What's the problem?"

The problem is the commitment was to tickets, not outcomes.

I've seen teams spend six months building features customers never adopted because nobody circled back to check. The roadmap said build it. Tickets got completed. Cards moved. Success!

Except customers are still complaining about the same problems they were six months ago.

Teams get busy without getting effective. Companies spend millions on engineering while their product stagnates. Everyone can be working hard, following the process, moving cards—and still failing.

Scenario 3: The Velocity Treadmill

Mid-stage startup, team under pressure. CEO wanted more features shipped. Head of product kept adding to the roadmap. Engineering manager kept saying they were going as fast as they could.

So they started measuring velocity. Story points per sprint. Baseline: 23. The goal, unstated but understood: increase it.

Next sprint: 26 points. Sprint after: 29. Progress!

Except here's what was happening:

- Inflating estimates so tickets felt bigger when completed

- Avoiding hard problems difficult to estimate

- Cutting corners on testing and documentation

- Splitting tickets more granularly to count them multiple times

Velocity went up. Quality went down. Time spent on foundational work—refactoring, performance, reliability—dropped to near zero. None of that showed up well in the velocity metric.

A year later the codebase was significantly harder to work in. Team constantly firefighting production issues. Actual feature delivery had slowed despite velocity charts still trending upward.

But for twelve months, every sprint review showed green metrics. Every card moved. Every number went up and to the right.

The process measured motion. Missed the fact that the motion was in circles.

How to Escape the Card-Movement Trap

1. Instrument outcomes, not just outputs

For every feature you ship, define what customer behavior you expect to change. Then measure whether it changed.

- Built an export feature? Track how many users export, how often, whether they come back.

- Improved onboarding? Track activation rates and time-to-value.

- Fixed performance issues? Measure actual load times for real users.

Put these metrics in your sprint reviews. Make them as visible as your velocity chart.

2. Make outcome hypotheses explicit

Before a ticket goes into a sprint, write one sentence: "We believe this will cause [specific user behavior change] because [reason]."

Most teams can't do this. They build tickets because they seem important, or a stakeholder asked, or they're on the roadmap.

If you can't articulate the expected outcome, you're guessing. Sometimes you have to guess. But at least be honest about it.

3. Conduct outcome retrospectives

Two weeks after a feature ships, ask: Did it do what we thought it would?

Not "Did we ship it?" Not "Did it work technically?"

Did it change user behavior in the way we expected?

If yes—what can we learn? If no—also great. What can we learn?

This practice is uncomfortable because it surfaces how often we're wrong. That discomfort is useful.

4. Limit work-in-progress at the outcome level, not the ticket level

Instead of "No more than 3 cards in development," try "No more than 2 customer outcomes in flight at once."

An outcome might be "Sales reps can identify at-risk customers." That might span eight tickets across three sprints. That's one in-progress outcome.

Finish things that matter before starting new things that matter.

5. Change your standup questions

Instead of:

- What card did you work on yesterday?

- What card will you work on today?

- Are any cards blocked?

Try:

- What outcome are you driving toward?

- What did you learn about whether our approach is working?

- What would help you deliver that outcome faster?

The first set optimizes for card movement. The second set optimizes for impact.

6. Stop celebrating card completion

Celebrate customer wins instead.

When a user emails "This new feature saved me three hours today"—that's worth celebrating.

When you ship ten story points? That's just Tuesday.

The Deeper Disease

The obsession with moving cards is a symptom: teams have lost connection to the mission.

When you're close to customers, you don't need elaborate metrics to know if you're succeeding. You hear it. You see it. You feel it.

When you're disconnected—three layers removed from the human trying to use your software—you need proxy metrics. Task boards. Velocity. Flow efficiency.

The process apparatus isn't the problem. It's a response to the problem.

The problem is that most teams have no feedback loop between the work they do and the value it creates.

So we invented a feedback loop between the work we do and the cards we move.

Cargo cult. We're building the airstrip and waiting for the planes. Doing the rituals of software development—standups, retrospectives, sprint reviews—without the substance.

The substance is talking to users. Watching them use your product. Measuring what they do, not what you ship. Staying brutally honest about whether the thing you built mattered.

Task boards can support that work. But they can't replace it.

A Practical Checklist: Are You Measuring Motion or Impact?

Warning signs you're optimizing for motion:

- Sprint reviews focus on how many tickets closed, not what changed for users

- You can't name the last three features you shipped and what impact they had

- Developers don't know who uses the features they build

- Product managers track velocity more closely than user behavior

- "Done" means "merged to main" not "validated with users"

- Teams are punished for missing velocity targets but not for shipping useless features

- Roadmaps are lists of features, not lists of customer problems

- Your metrics dashboard shows throughput and cycle time but no user outcomes

- Engineers can go weeks without talking to a customer or seeing real usage data

- Technical debt tickets get ignored because they don't "deliver value" (meaning: don't produce visible cards)

Signs you're measuring impact:

- Every feature has defined success metrics tracked after launch

- Sprint reviews include data on how shipped features are being used

- The team regularly kills features that aren't working

- Developers can explain who uses their work and why it matters

- "Done" includes validation, not just deployment

- Customer feedback directly influences next sprint's priorities

- You spend as much time instrumenting and analyzing as you do building

- Roadmaps are organized around customer outcomes, with features as means to ends

- Teams have direct access to usage data and customer conversations

- Slowing down to improve foundations is seen as legitimate high-value work

If you checked mostly the first list, you're in the card-movement trap. If you checked mostly the second, you're either exceptionally disciplined or lying to yourself.

Most teams are somewhere in between.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Most tickets don't matter.

You could probably delete 40% of your backlog and customers wouldn't notice. Another 40% delivers marginal value at best. Maybe 20% actually moves the needle.

But we treat all cards equally because the board is democratic. Every ticket gets its standup mention. Every story point counts the same.

A feature that causes 10,000 users to accomplish their goal faster is not the same as a refactoring ticket that makes one service slightly cleaner. A bug fix blocking your biggest customer is not the same as a tooltip alignment issue.

But on the board? Both just cards. Both move from left to right. Both feel like progress.

The way out is to be viciously honest about what actually matters. Stop pretending all work is equally valuable. Stop optimizing for how busy you look. Start optimizing for how much you matter to the humans using your product.

Smaller backlogs. Harder conversations about priorities. More time validating before building. More willingness to say "We shipped this and it didn't work, so we're killing it."

Treat the task board as a tool, not a scoreboard.

Remember that the work is not moving the card.

The work is changing someone's life, even just a little bit, in a way that matters to them.

Everything else is just motion.

The confusion between motion and progress isn't unique to Agile. But Agile methodology—with its emphasis on velocity, sprints, and visible workflow—has supercharged it. The original Agile Manifesto talked about working software and customer collaboration. What we got was Jira and standup theater.

I've spent twenty five years watching engineers try to fix broken processes. The ones who succeeded had data, allies, and patience. The ones who failed had opinions, frustration, and a retro slot.

Most of them were trapped in what I call Risk Management Theater and didn't even know

Is your organization performing control or practicing it?

The RMT Diagnostic is a 1-page PDF with 10 signs your team is trapped in Risk Management Theater. Takes 60 seconds. No certification required.

No spam. No "Agile tips." Just the diagnostic. Unsubscribe anytime.