Risk Management Theater

There's a specific moment every software developer knows. It's not the deploy that fails at 5:58 PM on a Friday, or the sprint planning meeting that devours an entire morning. It's subtler. It's that instant in standup when someone asks if you have blockers, and you say "no" — knowing you're lying.

You know the payments module is held together by three workarounds and a prayer. You know the integration test that was disabled "temporarily" eight months ago is hiding something nobody wants to discover. You know the estimate your tech lead gave the product director was based on nothing but social pressure and wishful thinking.

But you say "no blockers." And your colleague says "no blockers." And the standup ends in twelve minutes and the Scrum Master notes it was a productive standup.

The question that took me years to formulate correctly isn't "why do people lie in standup?" — that's obvious, people respond to incentives. The right question is: what kind of system turns honesty into a career risk?

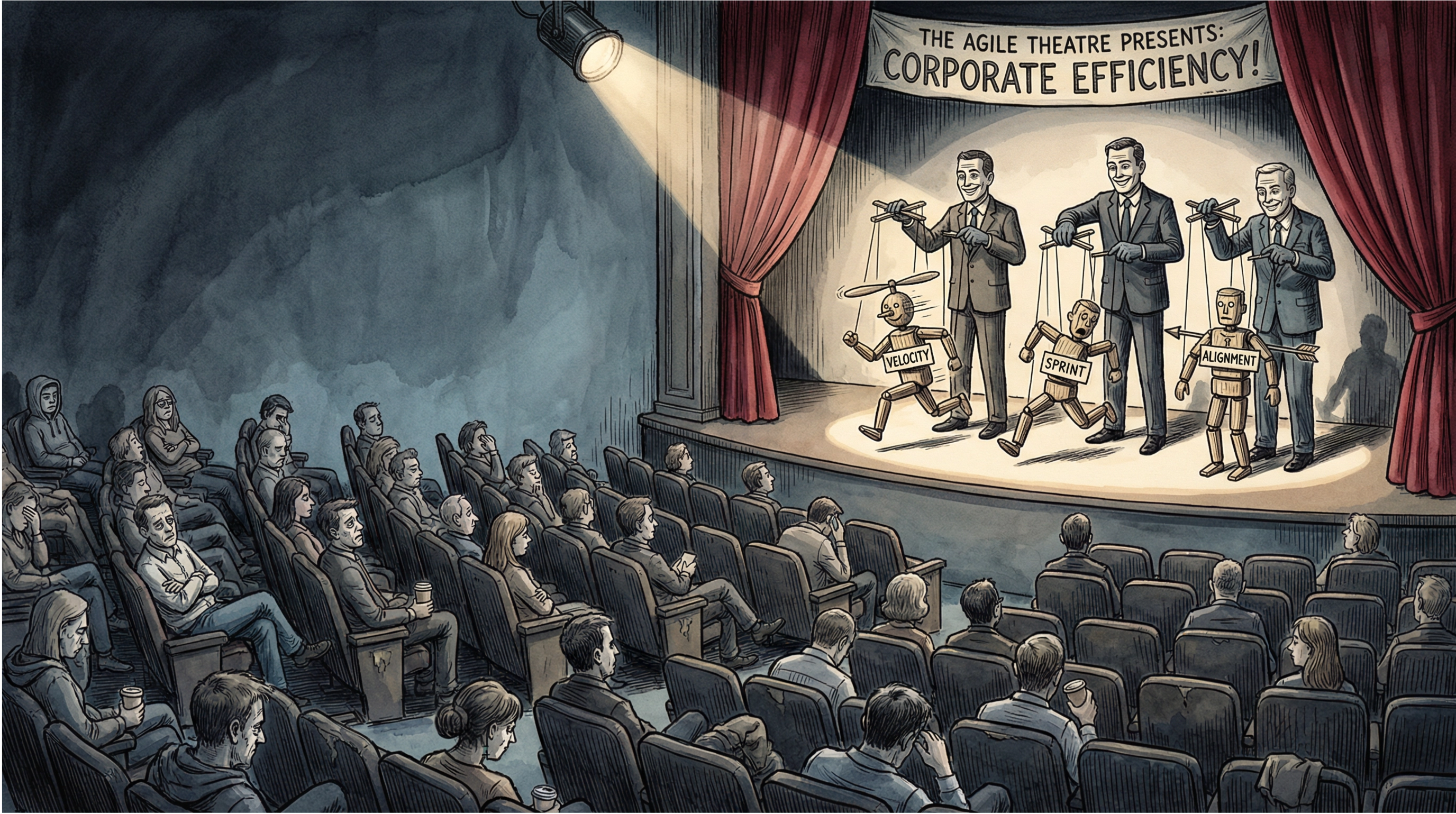

I call this phenomenon Risk Management Theater.

The term derives from "security theater" — the concept popularized by Bruce Schneier to describe security measures implemented in American airports after 9/11. Removing shoes. The 100ml liquid limit. The theater of inspection that makes passengers feel safe without necessarily being safer.

The analogy is precise. In software organizations, Risk Management Theater is the systematic practice of performing risk management without actually managing risk. It's the substitution of real control with visible control. It's the green dashboard that exists to calm stakeholders, not to reveal truth. It's the retrospective that produces 47 action items in six months and implements zero. It's the architecture of processes designed to distribute blame, not to make decisions.

What makes RMT particularly insidious is that it doesn't emerge from bad faith. Nobody wakes up thinking "today I'll implement dysfunctional processes that will destroy my team's ability to deliver software." RMT emerges organically from misaligned incentives, and once established, it self-perpetuates through mechanisms that seem rational to every individual involved.

Consider the basic dynamics of a standup. The format asks each person to answer three questions: what you did yesterday, what you'll do today, whether you have blockers. In theory, it's a coordination mechanism. In practice, in organizations with RMT, it's a performance ritual where admitting a blocker is equivalent to volunteering as the problem.

This happens because there's a fundamental asymmetry: if you identify a risk and the risk materializes, you're "the one who knew and didn't fix it." If you don't identify the risk and it materializes — well, who could have predicted? The rational choice, from an individual standpoint, is obvious. And when everyone makes the individually rational choice, the collective result is a system where risks are systematically made invisible.

The central mechanism of RMT is what I call liability distribution — the transformation of decision meetings into alignment meetings.

Observe the language. Nobody "decides" anything in meetings anymore. People "align." "Let's align with the product team." "We need to align expectations." "Are we aligned?"

Alignment sounds collaborative, consensual, mature. But ask yourself: if the meeting is to "align," where was the decision made? The answer, invariably, is: in a smaller room, with fewer witnesses, before the alignment meeting happened.

The alignment meeting doesn't exist to decide. It exists to create co-responsibility for what's already been decided. If the decision goes wrong, everyone who "aligned" shares the blame. It's a corporate hedging mechanism, not a decision-making mechanism.

I worked with a team at a financial institution — 25 developers, critical payments infrastructure — where this pattern was so pronounced that people developed a parallel vocabulary to navigate it. "Real meeting" meant an informal conversation at the coffee machine where actual decisions were made. "Official meeting" meant the subsequent theater where decisions were performed to generate the necessary paper trail.

The cost wasn't just time wasted in official meetings. It was the systematic erosion of the ability to discuss real problems in official forums. Meetings became spaces where you performed competence and consensus, not spaces where you solved problems. Problems were solved in parallel channels, informal, undocumented — which meant institutional knowledge lived in people's heads, not in the organization.

When those people left, the knowledge left with them. And the organization was perpetually surprised by problems that "nobody saw coming" — because the forums designed to surface problems had become forums designed to perform the absence of problems.

There's a specific tell that distinguishes organizations with RMT from healthy organizations: what happens when someone asks an uncomfortable question in a meeting.

I propose an experiment. In your next planning meeting, ask one of these three questions:

"What decision is actually open today?"

"What are we de-scoping to pay for this?"

"Which risk are we silently accepting right now?"

If people engage thoughtfully — if the questions generate genuine discussion and lead to concrete answers — you might be in a healthy environment. Congratulations. They're rare.

If people get uncomfortable. If there's a silence followed by someone changing the subject. If you're later told that those questions "weren't appropriate for that forum" or that you need to "be more solution-oriented" — your RMT is deeper than you think.

The theater survives because nobody names it. Naming it is a transgression because it breaks the collective agreement to not see what everyone sees. The person who names the theater becomes a problem to be managed, not an insight to be explored.

The surface symptoms of RMT are easy to list. I've compiled ten of them into a diagnostic tool that I'll share in a moment. But symptoms don't explain causes, and without understanding causes, you can't design interventions.

RMT has three root causes, and they're all structural.

The first is the accountability paradox. Organizations simultaneously demand accountability and punish those who surface problems. The result is predictable: people learn to be accountable for outputs they can control (attendance at ceremonies, production of artifacts, completion of tickets) rather than outcomes they can't (working software, solved user problems, sustainable systems). The metrics that get managed are the metrics that are safe to manage.

The second is the expertise inversion. In most software organizations, the people who understand the technical reality best — the engineers — have the least organizational power. The people with the most organizational power — directors, VPs, C-suite — are the furthest from technical reality. Information flows up through layers of translation and filtering, each layer adding optimism bias and removing uncomfortable details. By the time reality reaches decision-makers, it's been processed into a narrative that serves political needs, not truth needs.

The third is ceremony capture. Agile ceremonies were designed as lightweight mechanisms for coordination and reflection. Over time, in most organizations, they've been captured by control functions — transformed from tools that serve teams into tools that surveil teams. The daily standup becomes a daily status report. The retrospective becomes a blame-assignment mechanism. The demo becomes a performance review. Once ceremonies are captured, they can't serve their original purpose, but they can't be eliminated either because they're now load-bearing for the control structure.

I want to share five warning signs. There are ten in total — I've documented all of them in a diagnostic scorecard you can use with your team. But five is enough to recognize the pattern.

Sign one: "No blockers" is the default answer.

In your standups, how often does someone actually raise a blocker? Not a fake blocker that's really a status update ("I'm blocked waiting for the API docs"). A real blocker. Something that requires organizational intervention to resolve. Something uncomfortable.

If the answer is "rarely" or "never," you're not in a high-performing team with no problems. You're in a team where problems are socially discouraged. The absence of blockers in standup is not evidence that blockers don't exist. It's evidence that your standup has become a performance.

Sign two: decisions are made before meetings.

Pay attention to the flow of information in your organization. When a meeting is scheduled to "decide" something, has the decision already been made? Is the meeting actually a ratification ceremony? Who was in the room when the real decision happened, and who wasn't?

If decisions consistently happen in informal pre-meetings and formal meetings exist to create consensus theater around those decisions, you're not in a collaborative organization. You're in an organization with a shadow decision-making structure and a performance decision-making structure.

Sign three: dashboards are designed to reassure, not reveal.

Look at the dashboards in your organization. Who designed them? For what audience? What story do they tell?

If your dashboards are designed to make stakeholders feel good — if they're green by default and only go yellow or red when things are catastrophically wrong — they're not information tools. They're political tools. Real dashboards reveal uncomfortable truths. Theater dashboards reveal the absence of catastrophe and imply the presence of health.

Sign four: retrospectives don't change systems.

How many action items has your team generated in retrospectives over the past six months? How many of those were actually implemented? How many of those changed something structural about how your team works?

If your retrospectives consistently produce insights and inconsistently produce changes, you've got a reflection performance, not a reflection practice. Real retrospectives are uncomfortable. They surface systemic problems that require systemic solutions. Theater retrospectives surface symptoms and produce band-aids.

Sign five: "visibility" means surveillance.

When leadership asks for "visibility," what do they actually want? Do they want to understand the system — the architecture, the dependencies, the technical debt, the structural risks? Or do they want to understand the people — who's working on what, who's "productive," who's "underperforming"?

If visibility means knowing what every individual is doing but not knowing why the system keeps failing, you've got surveillance theater, not system understanding. The organization has optimized for tracking people, not for understanding problems.

If you recognized three or more of these signs, you're not crazy. You're not "not a team player." You're not "too negative." You're a craftsman trapped in a factory that has optimized for the appearance of production over actual production.

→ Take the full RMT Diagnostic

Ten signs. Five minutes. A score that tells you the truth about your environment.

The diagnostic won't fix your organization. Nothing in this article will fix your organization. But it will give you language. It will give you a framework. It will confirm that what you're seeing is real and has a name.

And naming things is the first step to changing them.

Risk Management Theater is one of twelve patterns of organizational dysfunction I've documented over twenty-three years in the software industry. The patterns interlock. RMT feeds into what I call "Metric Myopia" — the optimization of measurable proxies at the expense of unmeasurable outcomes. Metric Myopia feeds into "Ceremony Capture." Ceremony Capture reinforces RMT.

The full taxonomy is in a book I wrote called The Anti-Agile Manifesto. It includes the patterns, the diagnostic tools, the case studies, and — most importantly — the escape routes. Scripts for having the conversations that need to happen. Templates for implementing alternatives. An eight-week insurgency plan for changing your team's operating system from the inside.

But that's another conversation.

For now, take the diagnostic. See where you stand. And if your score is high, know that you're not alone — and you're not the problem.

The system is the problem. And systems can be changed.